Major Wyndham Harold Dickins was born in 1870 the son of Col Henry Francis Dickins and Lucy Catherine Tavener.

He had three brothers, two of whom were also members of the Lodge and the Regiment: Colonel Vernon William Frank Dickins DSO VD and Major Henry Percy Tavener Dickins. Their cousin, Henry Percy Faulkner Dickins, was also a member of the Lodge.

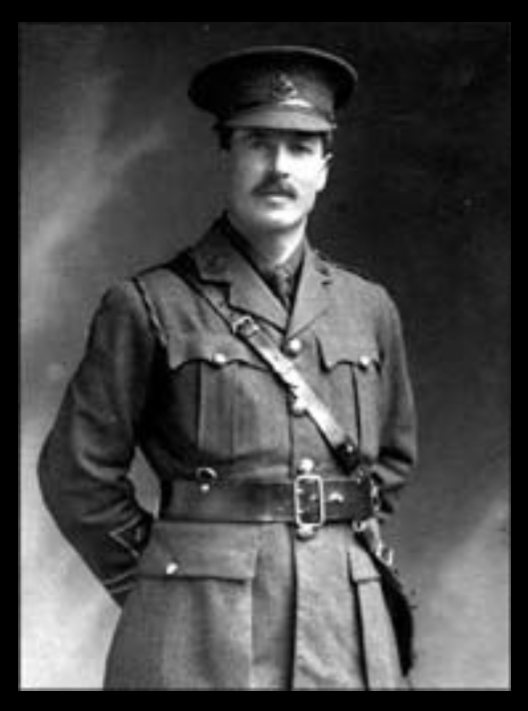

He was was a wine and spirit merchant in Philpot Lane in the City, in partnership with his brother Henry. He lived at Coombe Hall, East Grinstead. He married Beatrice Dickins and had two sons, Alec Francis Dickins and Kenneth Wyndham Dickins.

He was initiated in November 1894 at the age of 24. He resigned before rejoining in 1904. He served as Inner Guard in 1907.

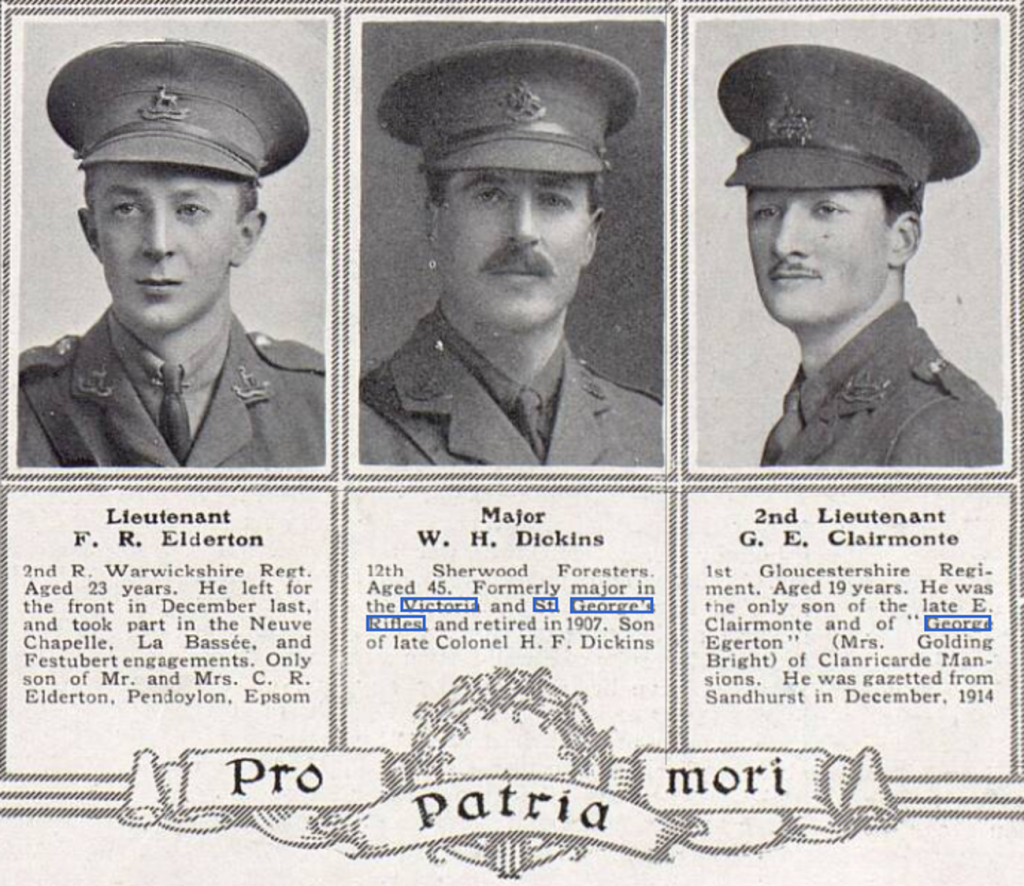

He was commissioned into the 6th Middlesex (St George’s) in July 1891 at the age of 21. He was promoted Lieutenant in March 1896, by which point the 1st and 6th Middlesex had merged to form the 1st Middlesex (Victoria and St George’s) and promoted again in September 1900. He was made an Hon Major in 1904. He resigned his commission in 1907, only to return to the Colours in 1914.

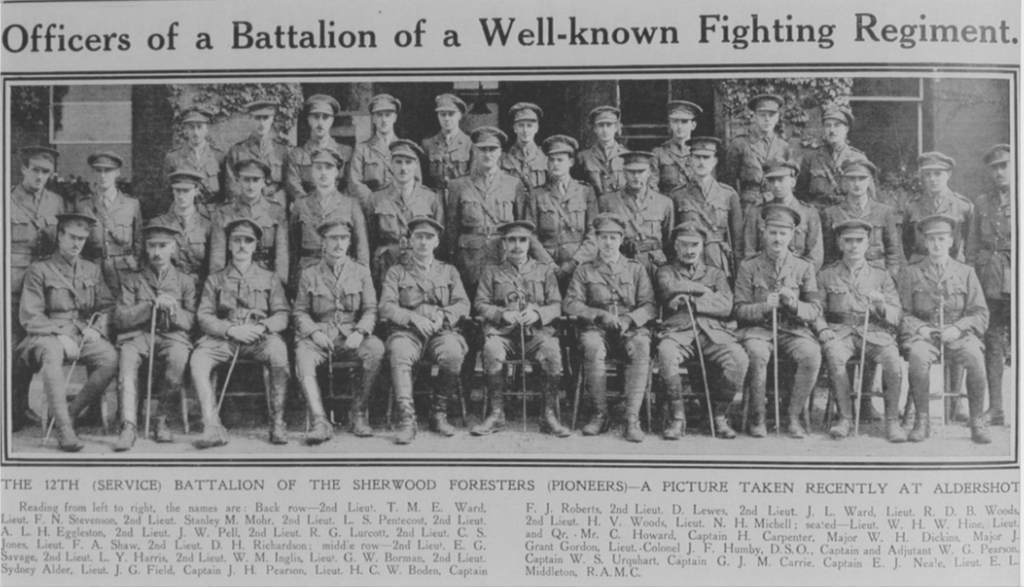

He was posted as a Captain in September 1914 to the newly formed Service Battalions and served in the 12th Bttn the Sherwood Foresters (Notts and Derby Regiment), a Pioneer Battalion in the 24th Division, part of Kitchener’s Third New Army, in the Great War. The Battalion went to France as part of the Division on 29 August 1915 and would later become famous for the production the “Wipers Times”, the trench newspaper which it began to print when in the town of Ypres in Belgium in 1916.

The Division concentrated in the area between Etaples and St Pol on 4 September 1915 and a few days later marched across France into the reserve for the British assault at Loos, going into action on 26 September 1915 and suffering heavy losses.

On 28 September 1915 Dickins died of wounds sustained at the Battle of Loos. He was 45.

Sister Margaret Blander, No 12 Ambulance Train, who nursed Captain Dickins through the final hours of his life, wrote to his widow after his death:

“…Your husband was brought on my train on the 27th September about 7p.m. He had a gunshot wound of his back, the wound in itself was small, but the spine must have been injured, as his legs were both paralysed. We got him made comfortable on his bed, he himself saying that he wanted nothing more now than a drink of water. He suffered no pain. He had sips of milk, water, and beef tea. About 10:00p.m. he fell asleep and slept about one hour. He did not sleep again, but said he had no pain, only thirsty, and he drank quite a lot, but would have nothing but water. He would have talked on, but I tried to get him over to sleep again, thinking a sleep would do so much for him. The only thing he was thinking of was the thought of getting home. He knew he was critically ill and asked me if I thought he should ever be able to cross over. Then he told me if I just gave him one other drink, he felt like sleeping. I gave him his drink, and he had only finished it when I saw a change and he just quietly breathed his last. There was no struggle, nothing could have been more peaceful. He never spoke again. His face was beautiful in it’s calmness and he looked at peace. He died about 10:00a.m. on the morning of the 28th September…

How often I think of the mothers, the wives and the sweethearts that are left to wait at home. I dread to think of England, it is a land of sorrow and mourning…”

He was one of five members of the Lodge to give their lives in the Great War.

(Maj W H Dickins seated fourth from left)